Going Long on the Vagus nerve: Startups Re-discover the Autonomic Neuromodulation Goldmine

Published on June 04, 2021

Electrical stimulation of the Vagus nerve to treat chronic disease has been around for 35 years, with mixed success. Fifteen ventures, as many therapeutic areas, and billions of dollars later, a new wave of breakthrough devices targeting areas like auto-immune diseases and diabetes is emerging. This post expands on a recent STAT article about companies in the field, looking deeper into the history and further into the future of vagal nerve stimulation devices.

Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) therapies promise a revolutionary alternative to pharmaceutical treatment for chronic diseases. By electrically stimulating the Vagus nerve, wearable or implanted devices could modulate the activity of the brain and other organs more precisely, conveniently, and with fewer side effects than drugs.

The field has come a long way since the first commercial venture (Cyberonics) was founded in 1987 to develop an implantable vagal nerve stimulator for epilepsy. The Feinstein Institute, DARPA, and the pharmaceutical giant GSK have all made significant R&D investments in bioelectronic medicine. There have been more than a dozen spinoffs from these R&D efforts, but few have had made it past the clinical stage.

As of 2021, only four Vagus nerve devices have made it to market. Patients can only access them in situations where drugs do not work (refractory epilepsy or treatment-resistant depression for example). Payers have been late to the party and have sometimes withdrawn coverage after initially offering it, meaning that health insurance often does not pay for treatment.

This hasn't deterred new entrants, like Nēsos, Spark, or GSK's venture Galvani Bioelectronics, all set up after 2016. They have uncovered lucrative new therapeutic areas and devised more precise ways of stimulating the system. While the early ventures focused on cardiovascular illnesses, depression, and epilepsy, the newer players have their sights set on diabetes or autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

Strictly speaking, not all the companies featured in this post target the Vagus nerve; some target the sympathetic side of the system, or its naturally occurring sensors. CVRx, for example, modulates the autonomic nervous system by stimulating the carotid body. Galvani is working on other autonomic nerves in addition to the Vagus, often choosing to modulate sympathetic nerves closer to their target organ.

The Science

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), which flips the body between the 'fight or flight' and 'rest and digest' states connects to all the major organs and modulates their function through electrical impulses. This twinned system regulates all biological functions: Breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, food intake, metabolism, and even immunity.

The Vagus nerve is the single long nerve that makes up the 'rest and digest' arm and connects with nearly every organ. But it isn't just a straightforward conduit that transmits information top-down from the brain to the organs. It is a bi-directional information superhighway, that also picks up signals from organs and from receptors that monitor the blood for chemical signals and passes them to the brain in a feedback loop. The 'fight or flight' arm of the autonomic nervous system is organized differently, with a chain of nerve nodes along the spinal cord leading to a dedicated nerve for each organ.

This makes the autonomic nervous system a natural target for many chronic diseases. If a device stimulates the appropriate fibers of the Vagus nerve in the correct location, it can selectively influence afferent (towards the brain) or efferent (towards the organs) signaling. A device placed at the neck or the ear, stimulating for a few minutes every day could influence metabolism or immunity to treat a host of conditions.

Vagus nerve and ANS ventures (1987 to 2021)

The New Wave

'New' is relative in the VNS world. Timelines from startup to FDA clearance can easily stretch to a decade or even two.

Spark

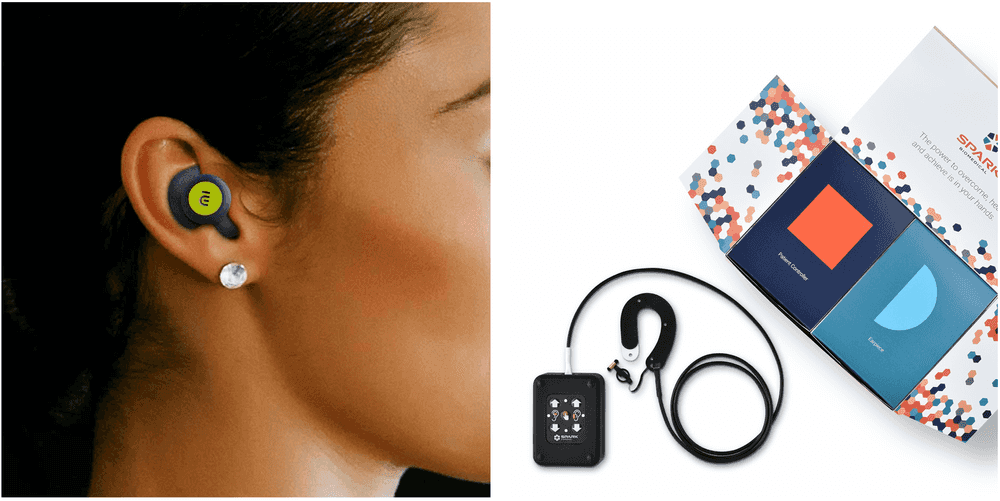

Founded in 2018, Spark Biomedical develops wearable neuromodulation devices that treat opioid withdrawal. The device wraps around the ear with a little earplug attachment that allows it to simultaneously stimulate the vagus nerve in the ear and the trigeminal nerve in front of the ear.

In a series of events that can only be described as fortune favoring the brave, the Spark team managed to get the right clinicians on board, find a suitable clinical trial site, secure funding for their first neonatal study, and receive breakthrough device status for this population in record time. They received their first FDA clearance for their use in adults in January 2021 and are now working towards approval to treat opioid withdrawal in newborns. Reimbursement or insurance coverage for their therapy is still a few years away, and the adult device is currently available on a self-pay or charitable use basis.

Although there is no public information about the company's funding aside from an SBIR grant, the team should be able to garner substantial investor interest given their rapid achievement of milestones and the huge unmet need for the product due to the ongoing US opioid crisis.

The idea of stimulating the Vagus nerve at the ear is not new. Cerbomed received approval in Europe (CE marking) for the treatment of epilepsy, depression, and pain through a patient-controlled earpiece-mounted vagal nerve stimulator in 2012, but the company has since fallen off the VNS map.

The Nēsos (left) and Spark (right) devices that stimulate the vagus nerve at the ear. Images from the Nēsos and Spark websites.

The Nēsos (left) and Spark (right) devices that stimulate the vagus nerve at the ear. Images from the Nēsos and Spark websites.

Nēsos

Nēsos, founded in 2016, is the brainchild of Nevro founder Konstantinos Alataris. With $16M in funding so far, the company received breakthrough device status from FDA for their earbud-like non-invasive vagal nerve stimulator. The device is used to provide 'e-mmunotherapy' and worn for a few minutes every day.

The company completed a pilot study for rheumatoid arthritis, an auto-immune disease that is currently treated with expensive biologic drugs and is moving on to pivotal trials. Migraine and depressive disorders could be next in the pipeline, along with a new fundraise.

Some of the early team is ex-Nevro, a company that went from founding to IPO in 8 short years, successfully competing with the giants of the spinal cord stimulation industry. A non-invasive device, combined with a commercially attractive launching indication and the founder's track record in the industry will likely take this start-up far.

Galvani Bioelectronics

Galvani is the pharmaceutical major GSK's high-profile bet on bioelectronic medicine. Founded in 2016, through a £540M partnership with Alphabet's Verily, Galvani has a much larger mandate than the typical VNS startup. Their focus appears to be less on the Vagus nerve, and more on the sympathetic arm of the ANS, which allows activation of multiple neuromodulation approaches for diseases like diabetes. The company has not yet announced a launching indication or therapeutic area but is probably well into their pilot human trials, targeting nerves to the spleen to treat inflammatory or auto-immune disease.

Galvani has taken a pharma-style pipeline approach to neuromodulation. They start with investment in R&D, incubating in-house research groups. Approaches that show promise on pre-clinical trials are moved forward to pilot clinical testing and then on to pivotal trials and FDA approval. Galvani has also formed numerous external research collaborations. Their parent GSK has a bioelectronics venture arm called 'Action Potential Ventures'. Verily was originally intended to provide some of the cutting-edge electronics capabilities for the nerve interfaces, but Galvani has also licensed devices from Nuviant medial and Enteromedics.

Other than the recent news about the firing of chairman Moncef Slaoui, Galvani has kept a low profile since its launch in 2016. This company may well be one to watch, given its lineage and funding.

BIOS

BIOS positions itself as a software platform rather than a neuromodulation startup. Founded in 2015, with $5.6M in funding so far, the team has built a machine learning platform off weeks of data collected from vagal nerve cuff electrodes in swine. While working on characterizing this data to discover biomarkers for chronic cardiac or respiratory disease, their larger goal is to provide a read-write interface to the Vagus nerve and the sympathetic chains around the spine so that pharma or other medical devices can discover biomarkers or implement closed-loop neuromodulation. All steps involve a heavy dose of machine learning magic.

BIOS' current team is short on both clinical expertise and industry experience and will likely be taken more seriously once they pass a regulatory milestone or make it to a clinical study.

The Old Guard

Companies founded in the 2000s are now making waves in ANS neuromodulation.

Setpoint

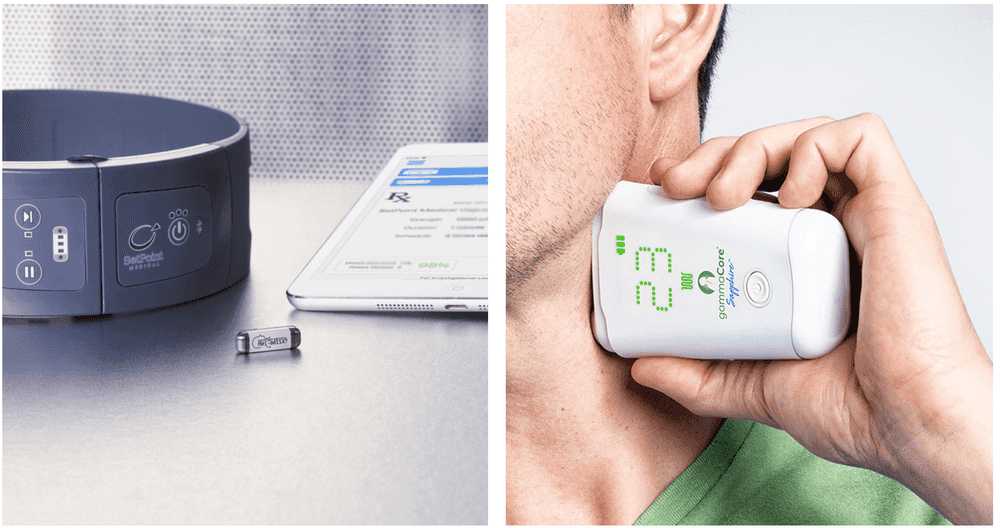

10 years older than Nēsos, Setpoint Medical is also going after the same disease -- rheumatoid arthritis. They also recently (October 2020) received a breakthrough device designation and are now in trials. Setpoint's device is a pill-sized, wireless, remotely rechargeable stimulator implanted near the carotid artery in the neck. The company also has a renowned co-founder in Kevin Tracey. Tracey's research group at the Feinstein Institute pioneered the science of controlling the immune system through the Vagus nerve.

Having raised $216M to date, Setpoint appears well-funded, but the costs and timelines of clinical testing for an implanted device are much higher than a non-invasive device. Once they get approved by FDA, they will still need to convince payers to shell out $30,000 plus the cost of surgery. On balance, this is still far more cost-effective than the expensive biologic drugs currently used to treat the disease. When biosimilars or 'generic' versions of the biologics become available in the US in 2023, this pricing may be harder to justify, especially if the device is only approved for treatment alongside drugs.

They are aiming for multiple inflammatory disorders, an enormous potential market. Setpoint's website indicates that 'Rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, multiple sclerosis and heart disease all share a common cause: Inflammation.' To realize this value, Setpoint will have to demonstrate that their implanted devices perform significantly better in trials than their non-invasive counterparts.

The Setpoint implantable wireless stimulator (left) and Electrocore's non-invasive Gammacore device (right). Images from the Setpoint Medical and Electrocore websites.

The Setpoint implantable wireless stimulator (left) and Electrocore's non-invasive Gammacore device (right). Images from the Setpoint Medical and Electrocore websites.

Electrocore

Electrocore, founded in 2005, received FDA approvals in rapid succession from 2017 through 2021 for their non-invasive vagal nerve stimulator to treat and prevent migraine and cluster headache. They have also achieved significant reimbursement milestones in the US and are making headway in the UK, meaning that their therapy is often reimbursed by insurers. The company's website is transparent about its pipeline, which includes several neurological and gastrointestinal disorders.

When applied to the neck for a few minutes each day, the device purportedly stimulates the Vagus nerve at the carotid in an afferent direction — meaning that it influences signals going towards the brain. Skeptics question whether the device affects the Vagus nerve at all, or has an alternative mechanism of action, as clinical trials have not shown that the stimulation produces the side effects commonly associated with implanted VNS devices.

Still, Electrocore is one of only two vagal nerve stimulation companies to have made it this far. The other is Livanova. Both companies are publicly traded, and Electrocore is a fair distance from profitability, with net annual sales at around $3.5M.

MicroTransponder

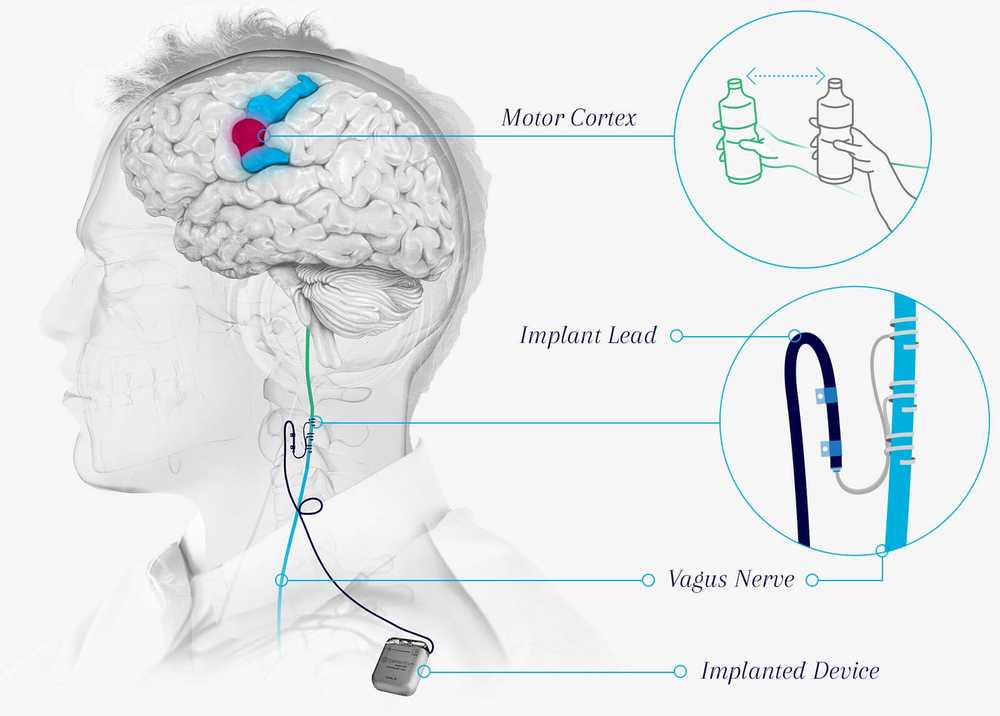

Founded in 2007, MicroTransponder recently announced the positive clinical trial results for its 'paired VNS' therapy for stroke rehabilitation. The device is an implanted vagal nerve stimulator that is activated during rehabilitation therapy to improve recovery of motor functions.

As part of ongoing clinical trials, the Dallas-based company pairs the same device with headphones for the treatment of Tinnitus. Neither therapy is approved by the FDA yet, and the long interval between development and commercialization means that the design of the cuff electrode with the implantable pulse generator could be outdated by the time the device comes to market.

Microtransponder's implantable VNS system in trials for stroke rehabilitation. Image from the Microtransponder website.

Microtransponder's implantable VNS system in trials for stroke rehabilitation. Image from the Microtransponder website.

LivaNova

The oldest name in VNS, Livanova, was formed when Cyberonics (founded in 1987) merged with Sorin. Their implantable vagal nerve stimulator received FDA approval for the treatment of refractory epilepsy in 1997 and treatment-resistant depression in 2005. The US Centers for Medicaid and Medicare initially announced that would pay for the therapy in patients but then reversed their decision in a blow to the company and industry. 15 years later, the team hasn't given up on depression, and CMS finally agreed to reimburse the therapy in 2019. They recently kicked off a large (1000 patients, 100 hospitals) study with Verily life sciences for vagal nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Alphabet's connection is that 300 of these patients in a sub-study will use Verily's wearable device to monitor physiological parameters like sleep, breathing, and heart rate, and a 'Mood app' to record depressive episodes.

Meanwhile, the company's epilepsy neuromodulation business has done well, and the company is expected to be profitable next year, with Wall Street analysts talking of a 'turnaround story'. After a scathing letter from shareholders in October 2020, Livanova will probably move faster to shed the cardiovascular business that it inherited from Sorin, and focus more squarely on neuromodulation.

CVRx

CVRx, another prominent name in ANS neuromodulation, markets a 'Barostimulation' device that does not directly modulate the vagus nerve or any nerve at all. It stimulates baroreceptors in the wall of the carotid artery, which in turn restores autonomic balance, reducing blood pressure and ameliorating the symptoms of systolic heart failure.

Founded in 2001, the company has an interesting backstory. It pivoted from hypertension to cardiac failure in 2006 and then went on to innovate by working with FDA through a unique clinical trial design; finally achieving breakthrough device status, FDA approval, and reimbursement twenty years after it was set up.

PINS Medical

Beijing PINS Medical's VNS device has been approved for the treatment of refractory epilepsy in China sine 2016. The company markets a vagal nerve cuff electrode with an implantable pulse generator. As of 2019, the device was used by nearly 300 patients in 60 hospitals.

The Ghosts

VNS devices have not made it to the market in some key therapeutic areas.

BioControl

Israel-based Biocontrol Medical developed the Cardiofit vagal nerve stimulator to treat cardiac failure. Pre-clinical and early clinical trials were encouraging but the company's 700-patient pivotal clinical trial failed to show that the treatment worked as intended. The company shuttered in 2016, following the failure of its famous INNOVATE-HF trial. Companies like CVRx used the learnings from INNOVATE-HF and Boston Scientific's parallel NECTAR-HF trial to select patients more carefully for their clinical studies.

Transneuronix

Founded in 1995, Transneuronix had developed a 'gastric pacing' device, whose mechanisms of action might have included VNS. The company was acquired by Medtronic in 2005 for USD 260 MM before it completed its pivotal trial in the US. It's not clear if the trial succeeded or if Medtronic is marketing the device or modifying it for other indications.

Enteromedics

Like Transneuronix, Enteromedics had a stomach pacemaker called vBloc, which claimed to treat obesity by blocking conduction in the vagus nerve around the stomach. In 2015 the device received FDA approval for weight reduction, despite mixed performance in clinical trials. IN 2017, a cost-effectiveness study of vBloc therapy for obesity showed that the therapy was likely to be good value for money in certain subsets of individuals. But there was no clear path to national reimbursement coverage and switched to 'prior authorization' to get patients to pay for one-off use.

Recent research casts doubt on the mechanism of action of the vBloc device, indicating that it may work through mechanisms other than VNS. In 2017, the company changed its name to Reshape, pivoting to 'a full-scale provider of medical devices to address the continuum of care for obesity and its associated health conditions' meaning that the company offers multiple obesity-related solutions unrelated to neuromodulation.

Despite the failures, vagal nerve stimulation seems to be picking up pace again, with new research directions and therapeutic areas. Researchers are currently focused on finding ways to stimulate the nerve more precisely, targeting well-defined nerve fiber subtypes. The expansion of VNS into areas lie auto-immune diseases, opioid addiction, and diabetes means that neuromodulation could eventually gain a foothold in some of Big Pharma's biggest markets. If device-makers can convince payers that the technology is cost-effective, this might be the decade when VNS finally takes off.

If you like it, share it!